Heroes

Suzanne Bacal

Suzanne Bacal focused her passion for the rights of people with disabilities on their inclusion and integration into all aspects of community living. An articulate advocate and skilled writer, her insightful and powerful letters to the editor were often published.

“There will always be obstacles. Conquer the ones inside and you can conquer the ones outside.”

-Suzanne Bacal

After graduating from Hofstra University and earning her master’s degree from the University of Miami, Bacal joined Liberty Resources, when it was called Resources for Living Independently, as the Coordinator of Community Outreach and Education. She was editor of Liberty Works for several years.

Bacal worked with the Ventilator Assisted Children Program at Children’s Hospital in Philadelphia as an adviser. She was instrumental in saving funding for the state’s Ventilator Dependent Children’s Home Program in the mid-1990s, helping to organize a silent protest of ventilator assisted children and their families at the state capital. With the aid of the Public Access Law Center, Bacal initiated a class-action lawsuit against SEPTA to improve paratransit services for people with disabilities.

Bacal spoke at workshops and conferences regularly, calling for better access, fuller employment and inclusion in the community for people with disabilities.

At the time of her death in January 2000, Bacal was the longest-tenured employee of Liberty Resources. She was 42.

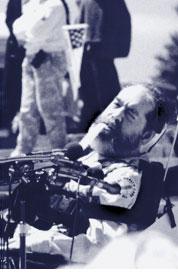

Justin Dart, Jr.

Justin Dart, Jr. contracted polio at the age of 18. He nearly died and, upon recovery, required a wheelchair for mobility. Rather than grieving about his condition, he expressed gratitude to the doctors who not only saved his life, but “made it worth saving.”

Refused a teaching certificate from a Texas University because of his disability, he instead became a successful businessman in Japan. A turning- point came during a visit to a Saigon “rehabilitation center” for children with polio, where, he found children left on concrete floors to starve. The experience, Dart later said, “was like a branding iron burning…onto my soul.”

“…But ADA is only the beginning. It is not a solution. Rather, it is an essential foundation on which solutions will be constructed.”

-Justin Dart Jr.

He dedicated his life to the cause of civil rights for people with disabilities. As vice-chair of the National Council on the Handicapped, and later as chair of the President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities, he advocated for a single federal civil rights act for people with disabilities. Dart was on the dais when President Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) into law in 1990 and was a good friend and strong supporter for ADAPT activists.

Dart later co-founded an organization for defending the ADA and continued to support persons with disabilities through lecturing and advocacy work. He will always be known as the father of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Edward V. Roberts

A polio survivor and respiratory quadriplegic, Edward V. Roberts’ doctor predicted he would live life like “a vegetable.” Instead, he was inspired by his disability to transform not only his life but the lives of thousands of other persons with disabilities.

“Get political or die, or go to a nursing home. If you’re not part of the political process, people will be talking for you.”

-Edward V. Roberts

Determined to attend college, he was admitted to the University of California at Berkeley where he lived in a hospital because dormitories were inaccessible. A newspaper article about his plight led to other students with disabilities being admitted to the school, and the group’s advocacy resulted in the Physically Disabled Students Program (PDSP) – the prototype for modern independent living centers. The program led to the founding of the Center for Independent Living (CIL), dedicated to supporting people with disabilities in achieving their independence. Roberts served as its first executive director.

Roberts went on to found nine additional independent living centers in the U.S., creating an independent living movement that became unstoppable. He then turned his attention to other countries, founding international organizations for people with disabilities, as well as helping to organize several independent living centers around the world. By the time he died in 1995, he had traveled more than one million miles to advocate for supporting people with disabilities in their efforts to lead independent lives. He will always be remembered as the father of the independent living movement.

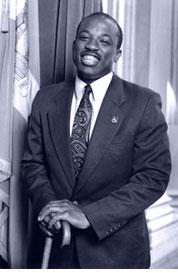

Oliver Jordan

Oliver Jordan was determined not to let cerebral palsy define him. Raised by a loving foster mother, Jordan was encouraged to follow his dream to make a difference – especially in the lives of children with disabilities.

With boundless drive and determination, Jordan became a respected advocate for people with disabilities in Philadelphia. Working for and with Philadelphia’s government and agencies after graduating from Temple University, Jordan spearheaded the first Youth with Disabilities Awareness Day in 1991 – matching children and professionals with disabilities for mentoring. He served as Managing Director of the Mayor’s Commission for People with Disabilities and was also instrumental in providing access for the deaf to the city’s 911 emergency phone system.

He was passionate about being involved in his community: for the Special Olympics Buddy Central Management Team, he helped recruit more than 10,000 volunteers; he became a Big Brother to a child he later adopted and he hosted the monthly Community Action Magazine radio program on WDAS-FM.

Jordan was also active in the early stages of Liberty Resources, when it was called Resources for Living Independently Center, serving on the first Board of Directors. He died in 2002 at the age of 42, leaving a legacy of caring and achievement in improving the lives of people with disabilities.